The Case for Human-Written Code in LLM Training

Why human-authored code remains essential for building reliable coding assistants — and where synthetic data falls short.

Pletava Team

Engineering

Introduction

As LLM-powered coding assistants become mainstream — tools like GitHub Copilot, Cursor, and Claude are now used daily by millions of developers — a critical question has emerged: can we train these models entirely on synthetic or auto-generated code, or do we still need human-written examples?

The temptation to rely on synthetic data is understandable. It's cheap, scalable, and can be generated in virtually unlimited quantities. But the evidence is clear: human-authored code remains essential for building models that are accurate, reliable, and genuinely useful in real-world development workflows. Models trained primarily on synthetic data produce code that looks plausible but breaks in production, misses edge cases, and converges on generic patterns that experienced developers would never write.

This article explains why human-written code matters, where synthetic data falls short, and how to structure a training pipeline that gets the best of both worlds.

The Problem with Synthetic Code

AI-generated or synthetic code is tempting as a training data source because it's cheap and endlessly scalable. Need a million examples of Python functions? Generate them in hours. But the economics mask serious quality issues that compound during training.

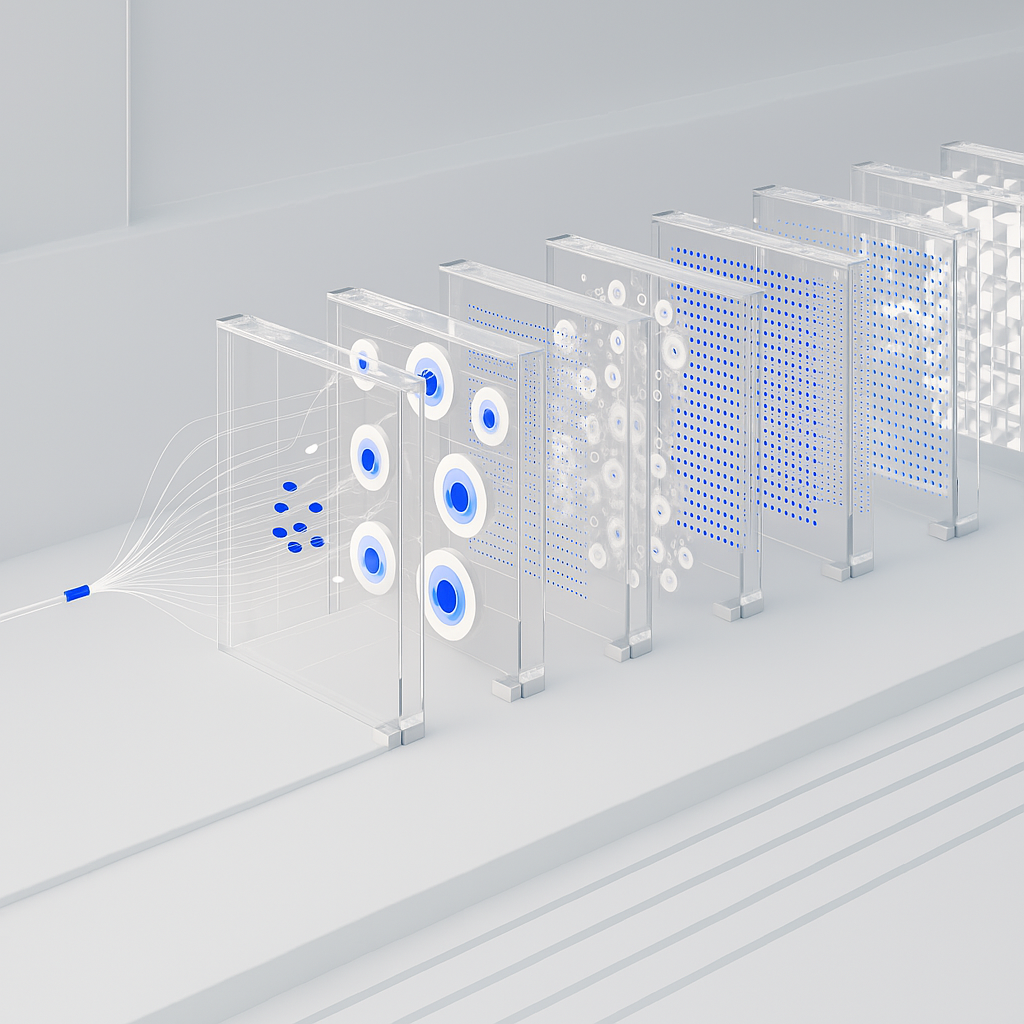

Model Collapse

Training models on their own outputs creates a feedback loop that researchers call "model collapse." Each generation amplifies biases and errors from the previous one, while gradually losing the diversity and nuance of the original human-generated distribution. The result is a model that produces increasingly repetitive, generic, and homogeneous code.

Research from the University of Oxford and others has demonstrated this effect clearly: models trained recursively on their own outputs progressively lose ability across generations. The tails of the distribution — unusual but valid coding patterns, creative solutions, domain-specific idioms — are the first to disappear. After several generations, the model converges on a narrow set of "average" patterns that lack the richness of human code.

This isn't just a theoretical concern. Teams that have experimented with synthetic data amplification report measurable drops in model diversity and problem-solving capability, even when the synthetic data appears correct on the surface.

Lack of Real-World Context

Synthetic code is generated in isolation — it doesn't reflect the messy, complex reality of production systems. Real codebases are full of context that synthetic generators simply can't produce:

- Legacy patterns: Real systems evolve over years. Code coexists with deprecated APIs, backwards-compatibility shims, and incremental migrations. Understanding and working within these constraints is a core developer skill that models need to learn.

- Integration complexity: Production code interacts with databases, message queues, external APIs, authentication systems, caching layers, and monitoring infrastructure. Synthetic code typically demonstrates algorithms in isolation, missing the glue code that makes systems work together.

- Organizational conventions: Every team has its own coding standards, naming conventions, project structure, and architectural patterns. Human code reflects these conventions; synthetic code defaults to generic patterns that may not fit any particular team's workflow.

- Workarounds and pragmatism: Real developers make pragmatic trade-offs — performance hacks for critical paths, temporary workarounds for upstream bugs, simplifications for code that doesn't need to be general. This practical decision-making is absent from synthetic code.

Surface-Level Correctness

AI-generated code often looks right but breaks in edge cases. It passes the "eyeball test" — the syntax is correct, the logic seems sound, the structure is clean. But it frequently misses:

- Boundary conditions: What happens with empty inputs, null values, maximum integer sizes, or unicode characters?

- Concurrency issues: Race conditions, deadlocks, and thread-safety problems that only manifest under load.

- Security vulnerabilities: SQL injection, path traversal, insecure deserialization, and other vulnerabilities that require security awareness to avoid.

- Performance pitfalls: N+1 queries, excessive memory allocation, blocking I/O in async contexts, and other patterns that cause problems at scale but work fine in small tests.

- Error handling: Synthetic code tends to handle the "happy path" well but neglect error cases, partial failures, and graceful degradation.

When models trained on this data generate code for developers, they reproduce these blind spots — creating a false sense of confidence in code that hasn't been truly vetted.

What Human-Written Code Brings

Authentic Problem-Solving Patterns

Human developers write code to solve real problems under real constraints — tight deadlines, limited resources, specific performance requirements, backwards-compatibility needs. This produces code that reflects genuine engineering trade-offs: when to optimize for readability vs. performance, when to use a simple approach vs. a scalable one, when to add abstraction vs. keep things concrete.

These decision-making patterns are exactly what coding assistants need to learn. A model that has only seen "textbook" solutions will suggest over-engineered abstractions for simple problems and under-engineered solutions for complex ones. Human code teaches models to calibrate their responses to the actual context.

Code Review Culture

Code from mature open-source projects and professional codebases has typically been reviewed, tested, and refined by multiple engineers. Pull request discussions, code review comments, and iterative improvements create a built-in quality signal. This isn't just about catching bugs — it's about establishing what "good code" looks like in practice.

When a model trains on code that has been through review, it absorbs not just the final implementation but the quality standards of the team. It learns that functions should be small and focused, that error messages should be helpful, that variable names should be descriptive, and that complex logic should be commented. These are soft quality signals that synthetic data generators don't encode.

Diverse Coding Styles

Different developers approach the same problem differently. One might use functional programming patterns, another might prefer object-oriented design, and a third might write procedural code. Some developers write verbose, heavily-commented code; others write terse, expressive code that relies on language idioms.

This diversity is a feature, not a bug. It helps models generalize better and offer varied solutions rather than converging on a single "correct" pattern. When a developer asks for help, the model can adapt its style to match the existing codebase rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all approach.

Synthetic data, by contrast, tends toward stylistic homogeneity. The generating model has its own style, and its outputs reflect that style consistently. Training on these outputs narrows the diversity of the downstream model.

Documentation and Context

Human code comes with a wealth of contextual information that synthetic code lacks: commit messages that explain why changes were made, pull request descriptions that provide business context, inline comments that document non-obvious decisions, README files that explain project structure and design philosophy, and API documentation that describes intended usage patterns.

This contextual information is invaluable for training models that need to understand not just what code does, but why it was written that way. A model that understands intent can provide better suggestions, more relevant explanations, and more appropriate trade-off recommendations.

Error Handling and Edge Cases

Experienced developers anticipate failure modes and write defensive code. They handle network timeouts, validate user input, check for null pointers, manage resource cleanup, and implement graceful degradation. This defensive programming style — born from years of debugging production incidents — is one of the most important things a coding model can learn.

Models trained on code that handles edge cases well will generate more robust, production-ready output. Those trained primarily on synthetic "happy path" code will produce fragile code that breaks at the first unexpected input.

The Data Quality Hierarchy

Not all human-written code is equal. Understanding the quality spectrum helps you make better decisions about how to weight different data sources in your training pipeline.

Tier 1: Expert-Written, Reviewed Code

Code from mature, well-maintained open-source projects (e.g., the Linux kernel, major web frameworks, widely-used libraries) or from dedicated data teams that produce training examples with explicit quality criteria. This code has been reviewed by multiple experienced engineers, tested extensively, and refined over time. It represents the gold standard of code quality.

Tier 1 data is the most expensive to produce and the hardest to scale, but it has the highest impact per example during training — especially during fine-tuning stages where quality matters most.

Tier 2: Professional Code

Code from working developers in production environments. This includes code from commercial projects, internal tools, and professional open-source contributions. Quality is generally good but variable — professional codebases include shortcuts, technical debt, and inconsistencies alongside well-crafted implementations.

Tier 2 data is valuable for teaching models about real-world development practices, including the imperfect but pragmatic decisions that characterize professional work.

Tier 3: Educational and Beginner Code

Code from tutorials, course assignments, coding challenges, and beginner projects. This code is typically clean and simple, with good structure and clear comments. However, it's limited in complexity and often doesn't reflect real-world application architecture or production concerns.

Tier 3 data is useful for teaching models fundamental concepts and for producing clear, explanatory code. It should be balanced with higher-tier data to prevent the model from producing overly simplistic solutions.

Tier 4: Unfiltered Open-Source Code

The long tail of code on GitHub, GitLab, and similar platforms. This includes everything from high-quality library code to abandoned student projects, auto-generated boilerplate, and code with known vulnerabilities. Massive volume but requires extensive curation — deduplication, quality filtering, license verification — to extract value.

Tier 4 data is primarily useful for pre-training, where volume helps the model learn syntax, patterns, and language fundamentals. It should not be the dominant source for fine-tuning.

Weighting Strategy

The best training pipelines draw from multiple tiers but weight them appropriately. A common approach is to use Tier 4 data for pre-training (broad coverage), Tier 2-3 data for continued pre-training (quality improvement), and Tier 1 data for fine-tuning (peak performance). This progressive refinement approach — starting broad and ending narrow — consistently produces better results than uniform mixing.

Practical Recommendations

Use Human Code as Your Quality Anchor

Even if synthetic data makes up the bulk of your pre-training corpus, fine-tune on curated human-written examples. The fine-tuning stage has a disproportionate impact on final model behavior — it's where the model learns to produce the kind of output that users actually want. Skimping on human data here means skimping on the quality of every response your model generates.

Invest in Data Curation

Quality filtering, deduplication, and annotation of human code yields better results than simply increasing dataset size. A smaller, well-curated dataset frequently outperforms a larger, noisy one. Build or invest in tooling for automated quality scoring, and pair it with human review for your highest-impact datasets.

Build Evaluation Sets from Human Code

Your benchmarks and test suites should reflect real-world coding patterns — otherwise you're optimizing for the wrong target. Synthetic benchmarks tend to test narrow capabilities in isolation; human-written benchmarks capture the integration, context-sensitivity, and pragmatism that matter in practice.

Maintain Data Freshness

Coding practices evolve continuously. New frameworks emerge, APIs change, best practices shift, and new language features get adopted. Regularly update your training data to include current patterns. A model trained exclusively on 2022-era code will miss important developments in async patterns, AI tooling integration, and modern framework conventions.

Consider Dedicated Data Teams

For organizations building production coding assistants, having engineers write targeted training examples for specific capabilities is a high-ROI investment. A small team of skilled developers producing 100 high-quality, expert-reviewed examples per week can have more impact on model quality than adding millions of lines of unfiltered open-source code.

Combine Human and Synthetic Data Thoughtfully

Synthetic data isn't worthless — it's useful for data augmentation, generating variations of human-written examples, creating training data for underrepresented patterns, and scaling pre-training corpora. The key is using it as a supplement to human data, not a replacement. Always validate synthetic data against human baselines, and monitor for signs of model collapse if synthetic data constitutes a large fraction of your training mix.

Conclusion

Synthetic data has its place — primarily for scaling pre-training and generating diverse variations. But human-written code remains the foundation of quality for coding LLMs. The models that perform best in practice are the ones trained on carefully curated human examples that reflect real development workflows, real engineering trade-offs, and real code quality standards.

The future of AI-assisted development doesn't depend on generating ever-larger volumes of synthetic code. It depends on investing in high-quality, human-authored training data that captures the full complexity and nuance of real-world software development. At Pletava, we believe this investment in data quality is what separates coding assistants that are genuinely useful from those that are merely impressive demos.

The organizations that recognize this — that treat training data as a first-class product, not a commoditized input — are the ones building the tools that developers will actually trust and rely on in their daily work.

Ready to build something great?

Let's discuss how Pletava can help you achieve your technology goals.

Schedule a Call